Prologue

Our next stop brings us back to Philadelphia and the Norristown High Speed Line, one of the most unique lines that qualify to be written about on this blog,1 which mixes multiple modes together in a special way and was one of the highest quality interurbans of the 1900s. The line still exists today, and despite its unique nature and long life, it has not aligned to any other mode in its operation, preserving its unique identity.

Overview

This 13.4 mile2 line runs northwest from 69th Street Transportation Center in Philadelphia Upper Darby, the same major hub that the 101 and 102 run out of. As mentioned in the post on the 101 and 102, this line is unique. It’s completely grade-separated, high floor, and uses third rail, but runs mostly single cars, has mostly on-board fare collection, and rather close stop spacing, compared to suburban heavy rail at least.3 You can debate over whether this can be called a tram, but that’s the whole point of this blog anyway!

The line heads out from triple tracked and four platformed 69th Street terminal past the yards of the Market-Frankford Line and the SEPTA Victory Division, made up of the 101/102 trolleys, Norristown High Speed Line, as well as buses serving the western suburbs. The line passes a few golf courses, ducking under and over a few roads until Penfield Station, where the line rises onto an embankment surrounded by residential suburbia and a few parks. Past Mill Road, the line returns to ground level and arrives at Wynnewood Road, which used to be triple tracked with an island platform. Just before Ardmore Junction, the line rises up again to pass over the SEPTA 103’s busway, a remnant of the former Red Arrow line.

Continuing to Haverford Station, Haverford College passes by on the right, with… another golf course on the left. Bryn Mawr is triple tracked, with an island platform and a side platform northbound, with the middle track being used for short turn service. It’s also here that the SEPTA Main Line4 really starts to overshadow the Norristown Line, running parallel to it, and often serving busier parts of town. They had actually only been about a mile apart since Ardmore, but are under half a mile apart here. The line then curves through a few more neighborhoods to reach Villanova University, where there is some of the most egregious stop spacing, with Stadium and Villanova Stations only 1000 feet apart, quite literally around a corner from each other.

Just past Villanova is also where the old main line to Strafford branched off, heading west while the route to Norristown turned north. The line crosses under the Main Line, and parallels I-476, heading northeast for a bit before turning back north to follow Montgomery Avenue. The houses are noticeably less dense here, and you quickly arrive at yet another golf course, next to Gulph Mills station, where there is a transfer to the 124/125 express routes to Center City. There’s a few office parks and a bit of suburban businesses with parking lots by Hughes Park and DeKalb Street, and then the line enters downtown Bridgeport, right across the Schuylkill River from Norristown. The two tracks merge into one and rise onto a high trestle above downtown and over the Manayunk/Norristown Regional Rail Line tracks to an elevated, two track island platform terminal at the Norristown Transportation Center, with a myriad of suburban bus connections.

The service patterns on this route are unique as well, with the September 2, 2019 schedule5 seeming to show Norristown Expresses inbound in the morning rush only, with locals from Hughes Park. The outbound morning rush had alternating locals to Norristown and Hughes Park, with a few random Bryn Mawr short turns thrown in for extra confusion. Midday service ran consistent Norristown Locals. Every other trip from about 3 in the afternoon until about 7 was a Hughes Park short turn, with a few random Bryn Mawr short turns thrown in inbound at the end of the rush. Saturday featured two random Bryn Mawr short turns in both directions, with one inbound in the morning and the rest in the afternoon, a random Norristown Express trip inbound in the afternoon, and a Norristown Limited trip outbound! These were rather common in the February 25, 2019 schedule, but disappeared on weekdays, along with the labeling on the map of which stops were served by them, with the random exception of DeKalb Street, meaning that nobody can tell which stops it serves in between the timepoints. Thankfully, Sunday was a bit more sane with only two Bryn Mawr short turns in the morning inbound, and a few sprinkled in in the afternoon.

The current Covid schedule features alternating Hughes Park short turns in the rushes, and two random Bryn Mawr short turns, with weekends consistent Norristown Locals.

Service patterns are a mess, so here’s a different schedule table format…6

| Stop: | Early Major Stop7 | Early Minor Stop8 | Bryn Mawr-Hughes Park | Norristown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start Time: | 4:00 | 4:00 | 4:00 | 4:00 |

| End Time: | 2:41 | 2:41 | 2:41 | 2:41 |

| Morning: | 25-20 minutes9 | 25-20 minutes | 25-20 minutes | 25-20 minutes |

| Morning Rush Inbound: | 5 & 15 minutes10 | 20 minutes | 8 & 12 minutes | 20 minutes |

| Morning Rush Outbound: | 10-5-10 minutes | 10-5-10 minutes | 10 minutes | 20 minutes |

| Midday: | 30 minutes | 30 minutes | 30 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Afternoon Inbound: | 10 minutes | 10 minutes | 10 minutes | 20 minutes |

| Afternoon Outbound: | 8 & 12 minutes | 8 & 12 minutes | 8 & 12 minutes | 20 minutes |

| Evening Rush Inbound: | 10 minutes | 10 minutes | 10 minutes | 20 minutes |

| Evening Rush Outbound: | 8 & 12 minutes | 8 & 12 minutes | 8 & 12 minutes | 20 minutes |

| Evening: | 15-30 minutes | 15-30 minutes | 15-30 minutes | 15-30 minutes |

| Saturday: | 20 minutes | 20 minutes | 20 minutes | 20 minutes |

| Sunday: | 30 minutes | 30 minutes | 30 minutes | 30 minutes |

The rolling stock consists of 26 1992-1993 ABB N-5 cars. Apparently ABB merged its railway rolling stock production with Daimler-Benz11 in 1996 to form Adtranz, a potentially more familiar name, which also manufactured the Market-Frankford Line’s rolling stock, before being bought by Bombardier in 2001. Two car trains run during rushes, with single cars at other times. The line is also standard gauge, differing from the (other) trolley lines and the Market Frankford Line, both of which use Pennsylvania Trolley Gauge, 5 ft and 2 1/4 in. Electrification is 600V DC.

Fares are the standard $2 with the SEPTA Key Travel Wallet, with one free transfer and $1 for transfers after that, or $2.50 with cash and no free transfers. There are fare gates at 69th Street and Norristown Transportation Center, but at the other stations fares are paid on board with a fare box on entry.

The line gets about 11,000 riders per weekday,12 but there’s a very noticeable difference between different stops, with the least used stop, County Line, getting only 14 riders per day.

History

Philadelphia and Western Railroad/way

You might be wondering how we ended up with this special line. The Philadelphia and Western Railroad was created in 1902, rumored to have been built to connect Philly with the Western Maryland Railroad in York, as part of a planned transcontinental along with the Pittsburgh and West Virginia, Wabash Railroad, Missouri Pacific Railroad, Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, and the Western Pacific Railroad by George Gould, though he denied it. In 1907, the line opened from 69th Street to what Wikipedia calls a “converted farmhouse” station near Strafford. The line was noted for its high quality construction, with no grade crossings, full double track, wide curves, grades of no more than 2.5%, heavy rails, and provisions for quad tracking. It was also electrified, which gave it an advantage over the parallel Pennsylvania Railroad Main Line in speed. The quality of the line promoted the rumors that it was actually part of the transcontinental, though I don’t think it was ever proven.

A Trolley Park was built in Haverford in 1907, and could fit 15,000 people, but was closed an embarrassing 2 years later due to competition from other trolley parks and bad management. The railway company itself also quickly got into financial trouble, reorganizing into the Philadelphia and Western Railway also in 1907, with the extension to York and Parkesburg officially cancelled in 1912.

In October 1911, the line was extended to across the street from the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Strafford Station station, today’s station of the same name on SEPTA’s Paoli/Thorndale Line, once it was clear the extension to Parkesburg and beyond was not happening.

This is also a good time to mention the insanely unique history of cars on the line. Apparently the first cars bought for the line were sold to San Francisco before ever running on the line, and the first cars to actually run on the line were a fleet of 22 wooden cars built by the St. Louis Car Company. They were 51 ft long, had reversible seats, smoking compartments, and bathrooms. They were initially equipped with bow collectors, and later trolley poles, in addition to contact shoes, for yard service and more flexibility.

As for the Norristown Branch, it opened in 1912, branching off at Villanova, and it quickly became far busier. The extension proved to be quite complicated to build due to the many grade crossings and high standards of the railroad. At Norristown, the line connected to the Lehigh Valley Transit Company which ran an interurban line from Allentown to 69th, along the P&W’s tracks.

3 steel cars were delivered in the early 1920’s but were limited to service to service to Strafford because they lacked trapdoors, needed at Norristown. 11 more cars were bought from Brill in 1924-1929, with a maximum speed of 44 miles per hour, and had baggage racks and doors between cars. These were known as “Strafford Cars” and remained in regular service until 1990.

With the electrification of the Main Line in 1915, the Cynwyd Line in 1930,14 and the coming electrification of the Manayunk/Norristown line, and all of the related speed increases, it was clear the P&W needed a complete makeover to compete with the railroads.

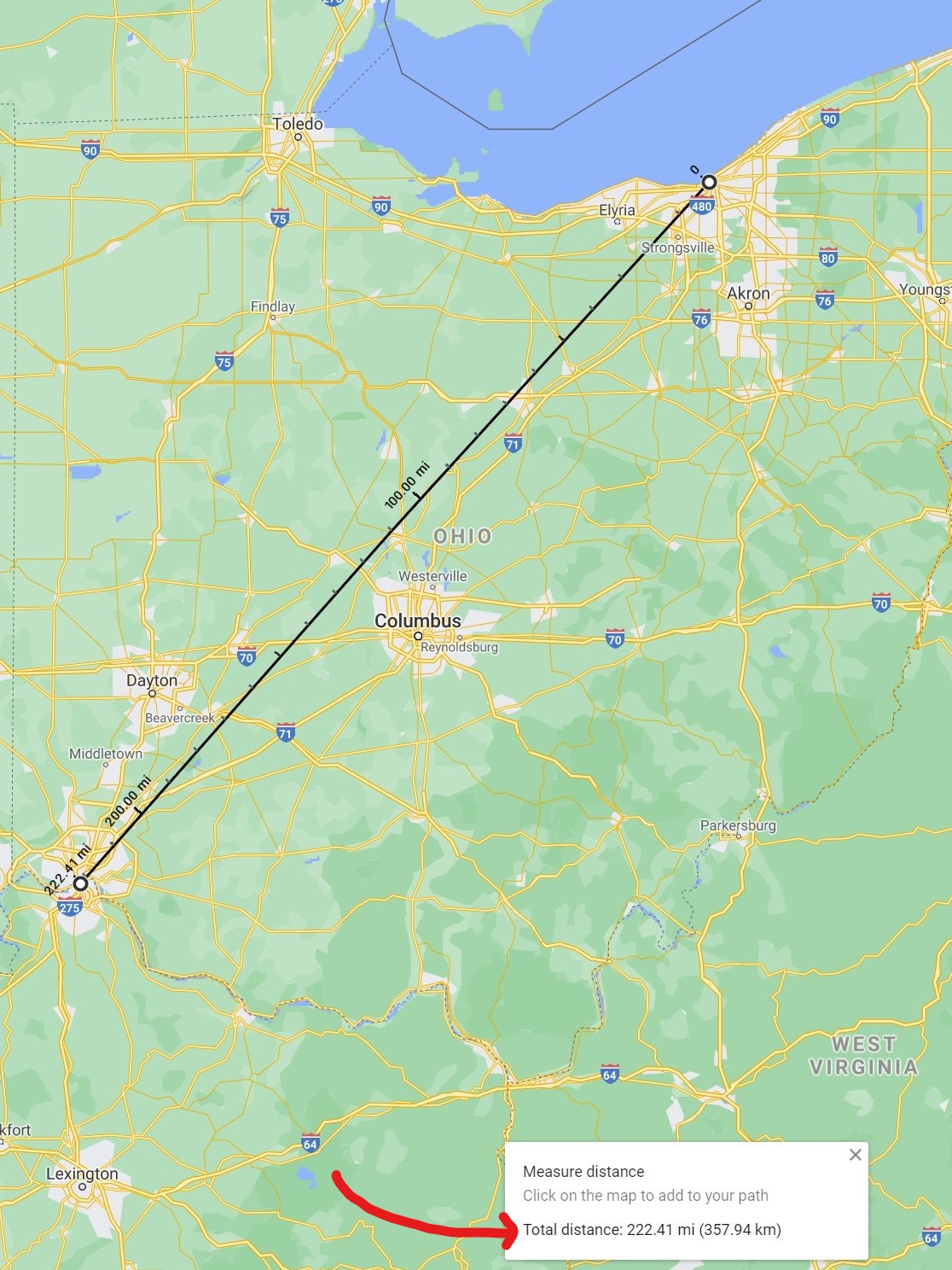

In 1930, Dr. Thomas Conway Jr15 gained control of the company, making plans for higher speed vehicles and service, based on his experience with the Cincinnati & Lake Erie Railroad, a high speed interurban between Cincinnati and Cleveland.16 One of the C&LE cars was shipped to Philadelphia for testing, and after elaborate testing in the University of Michigan’s wind tunnel, a final design was chosen, creating the Brill Bullets.

These 10 lightweight cars were capable of more than 80 miles per hour and dramatically reduced travel times, with the running time of expresses to Norristown dropping from 24 to 17 minutes, and the local running time from 28 to 20 minutes. Norristown was also rebuilt as a high level platform. The low speed Strafford Cars, less than 10 years old, were completely rebuilt from 1931 to 1935, losing trolley poles, trapdoors, and gaining a lower center of gravity by… having smaller wheels? Their top speed increased from 44 to 68 mph as a result. The original three steel cars were never rebuilt and were limited to rush hour local service on the Strafford Branch.

All of these improvements were not quite enough for the Strafford Line, with the last 1.74 miles west of St. David’s Station downgraded to single track in the mid 1930s. At this point, the railroad had apparently gained the nickname the “Poor & Weary”, and it filed for bankruptcy in 1934. There seemed to be confusion or something, because nothing much happened until World War II, when ridership ticked up again and the P&W somehow began turning a profit again.

Starting around 1943 our (nonpersonal) good friend Merritt H. Taylor started reaching for control over the profitable Norristown Line, reorganizing the company in 1946 back to become the Philadelphia and Western Railroad. The P&W was completely absorbed by Taylor’s Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company in 1953.

Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company

One of the first things the PSTC did was retire the never-upgraded cars from service, meaning all remaining cars were all high-speed. The Strafford Branch was finally cut in 1956, with the PSTC citing only 500 daily riders on the branch. Its replacement bus service on Conestoga Road is also gone today. The right of way is now the Radnor Trail.

With the dead weight of the Strafford Branch gone, the PSTC went all in on investments for the Norristown Line, bringing in the Electroliners from the Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad, removing their trolley poles, and rebranding them as Liberty Liners17 to fit with Philadelphia’s theming of… being American. These were streamlined, 4-section interurban cars built in 1941 by the St. Louis Car Company, numbered 801-802 and 803-804.18 801-802 was named “Valley Forge”, and 803-804 was named “Independence Hall”, because patriotism.

These regularly ran in service at over 90 mph on the North Shore, and reached 110 mph in tests, but the curvy and stop-heavy Norristown Line severely restricted their speeds, mostly reduced to just being extra fancy cars instead of the state-of-the-art high speed cars they were on the North Shore. They did continue to serve coffee and breakfast in the mornings and snacks in the afternoons.

After resisting pressure to work with public agencies for decades, in 1970, facing ever increasing costs, the PSTC sold the Norristown Line, 101/102, and its buses to SEPTA.

For a more detailed overview of the PSTC, including a look at the other Red Arrow lines, see the section of the post on the 101/102.

SEPTA

Just as with the 101/102, when SEPTA took over the PSTC, employees went on a strike to protest being part of a public company, lasting more than a month.

The Liberty Liners were retired in 1978 because of high power consumption and apparently being too heavy for the old rails.

In the 1990s, when the Strafford Cars and Bullets were going on 60 years old and falling apart, and the new N-5 cars were facing delays, SEPTA brought in 14 CTA 6000 series cars from Chicago, and 5 M-3 cars from the Market-Frankford Line to keep service alive. Interestingly, the M-3 cars needed to be regauged from PA Trolley gauge to standard gauge when going from a 100% heavy rail line to an ehhhh 50% light rail line, opposite of the guage name.

We couldn’t find any usable images of the CTA or MFL cars on the line, we recommend looking them up, otherwise modern images were also lacking.

In 2013, the line ended in Bridgeport for 4 months, with bus shuttles to Norristown to allow for repairs to the deteriorating bridge over the Schuylkill.

The long-time use of “Passenger Advance Lights”, making waiting passengers push a button to, well, light up a light and let the next operator know they should stop, was discontinued on December 7, 2020.

Future

An extension to the King of Prussia Mall19 and Valley Forge20 has been under planning since at least 2012. The spur would branch off between Hughes Park and DeKalb Street, interestingly with a wye, allowing service from both Norristown and 69th. The line is planned to be mostly elevated over suburban highways and streets, and stations that seem pretty fancy, based on the renders. It also stays fairly far away from neighborhoods due to a lot of opposition. In 2014, the roughly 4 mile line was estimated to cost $500 million, and since this is the US, a country known for its lack of currency inflation, the cost grew to $1 billion by 2018, and $2 billion by December 2020.

This extension has been sometimes criticized as excessive and misplaced, being advanced while SEPTA itself is usually short on cash and often struggles to supply proper frequency for its bus routes or renew rolling stock timely, and of course there are neighborhoods that would benefit more from rapid transit than this suburb.

It’s a bit worrying that I haven’t seen any hard frequency numbers besides “it will go up”, because the fleet is somewhat small at 26 cars, and also because there hasn’t really been much indication of how King of Prussia to 69th or KOP to Norristown services would work together with the main line. Capacity restraints with the only single track on the line at Norristown can also become a problem, hindering expresses. Overall I’d say it’s a good expansion, but there’s been a bit of confusion and a lot of cost ballooning.

Extra: The Lehigh Valley Transit Company

The beginnings of the Lehigh Valley Transit Company come from Albert Johnson, a street railway magnate who worked with systems in Cleveland, East Liverpool,21 and Brooklyn, who in 1893 made a plan for a line from New York City to Philadelphia via Allentown, calling his company the Lehigh Valley Traction Company. However, he died of a heart attack in 1901 at just 41, leaving behind a a bit of a mess, with the company reorganizing into the Lehigh Valley Transit Company. The route to New York cancelled was by the new owners by 1903.

After operating local service in Allentown for a while, the company opened a new line from Allentown to Chestnut Hill in 1903, connecting to Philadelphia Rapid Transit streetcars to Center City. In 1912, a new, faster route south from Allentown was opened, connecting to the P&W at Norristown and continuing on its tracks to 69th Street. Initially, the line ran with traditional, lower speed cars fitted with luxurious interiors with separate smoking and baggage sections and a bathroom. Streetcars ran with trolley poles to Norristown and switched to third rail from there to 69th. They made the trip in 2 hours and 15 minutes, described as a “dream” by the Morning Call.

The LVT also ran freight service, like many other interurbans of the time.

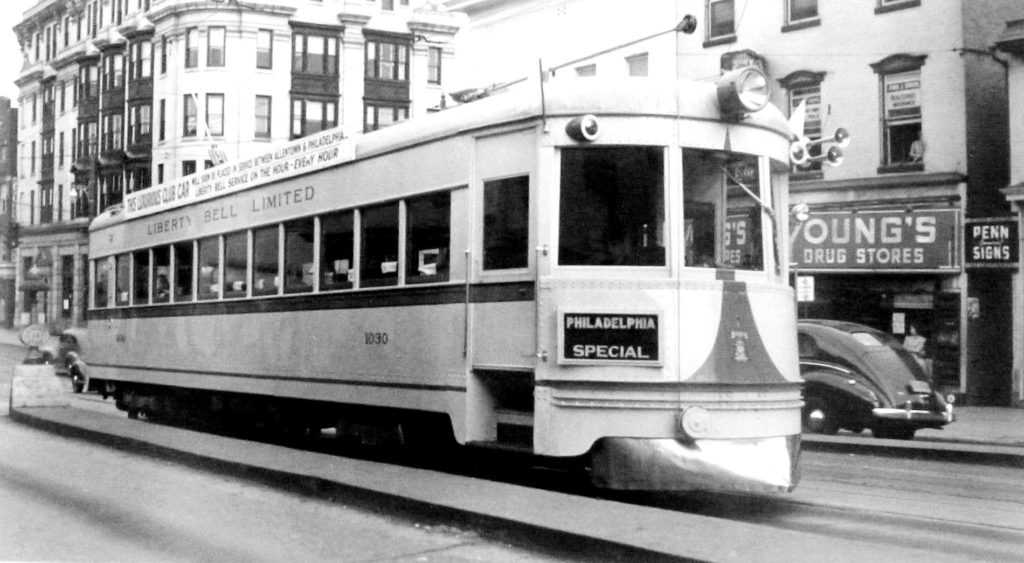

Like the P&W, though, the 1920s and 30s saw increases in competition from cars, with the old line to Chestnut Hill abandoned in 1926. Lightweight, high speed Red Devils from the abandoned-by-now Cincinnati & Lake Erie22 were brought in in 1939. These weren’t meant to be permanent, as the conversion to bus was seen as inevitable, but with the faster speeds, making the trip in 1 hour and 30 minutes, and the wartime rationing, the line made a comeback. After one of the cars was destroyed by a fire, another car was bought from the Indiana Railroad (55), another interuban, and became the fanciest car of the whole fleet (renumbered 1030), and is now preserved at the Seashore Trolley Museum.

After the war ended though, and with the continued rise in automobile use, the LVT really stopped caring about the line, and practically stopped maintaining it, in addition to cutting trains back to Norristown in 1949, forcing a transfer to the P&W’s trains. The line was completely abandoned in 1951.

The right of way from the line was quite varied, mostly single track with passing tracks, and a mix of high speed grade separated right of way, street running, and side-of-the-road running. A short portion of the right of way is preserved as the Liberty Bell Trail in Hatfield.

While the 1030 is in display condition at Seashore, hasty maintenance by LVT and aluminum-on-steel construction have caused major problems. Due to it being a landmark car, the museum is currently fundraising to get it in proper working order. Learn more here.

Analyzation

How effective is this mix of modes compared to simpler systems?

Frequency: Frequency seems… good enough in the rushes, morning, and evenings, though midday service, at every 30 minutes, is rather unacceptable. Saturdays are on the edge at every 20 minutes, and Sundays are lacking as well, at every 30 minutes. Weekends could be better, but considering the suburban nature of the line, middays are probably the only sector that really needs fixing.

Intermodality: As with the 101/102, transfers to the MFL are needed to get to Center City, which used to be terrible, but is being resolved with the SEPTA Key fare transformation. There are transfers to the 103 at Township Line Road and Ardmore Junction, the 106 in the Villanova area, as well as the 99 at DeKalb Street, besides the major hubs at 69th and Norristown and the tiny hub at Gulph Mills. As mentioned, the line parallels the Paoli/Thorndale Regional Rail line for a while, and ends at the Manayunk/Norristown Line, offering a cheaper and more frequent, if a bit slower alternative.

Character: As mentioned, there are no grade crossings, and although the curves are all gentle, there are a lot of them. Stations are, like every part on this line, unique. They’re an interesting mix of seemingly low effort, short, inaccessible platforms with small shelters and one or two benches and wastebaskets, but also with complex stairs, footbridges and underpasses, a consequence of its grade separation and third rail. Also, did I mention the golf courses? Wikipedia describes how the NSHL “played a pivotal role in the infrastructure of the 2013 US Open at the Merion Golf Club.” And guess what, the 1981 US Open was also held there!

Type

Given the high level boarding, third rail, and full grade separation, but 1 or 2 car trains with onboard fare collection, this is Lightweight Metro.23 The suburban character of the line, short trains, somewhat low frequencies, and relatively simple stations tend to make me think of it more as Suburban Light Rail that just happens to be high floor and use third rail, though it’s grade separated so there’s that.

We hope you have enjoyed this post, if you have any questions, comments, feedback? please do not hesitate to comment or contact us.

Sources

The images have been credited to their respective owners in the caption of each image

Due to the unprofessional nature of this blog, sources will be cited in a simple manner, with no formats yet. Sources used are:

- Google Maps

- Wikipedia

- Historic Aerials

- nycsubway.org

- SEPTA

- Internet Archive‘s Wayback Machine

- ISEPTAPHILLY

- Electric City Trolley Museum Collection

- Philadelphia Trolley Tracks

- The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia

- Metro Fandom Wiki on the Philadelphia and Western Railway Company

- Railfan Guides of the US on the Norristown High Speed Line

- Miles in Transit on the Stadium NSHL Station

- Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives

- SNAC Cooperative on the Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company

- I Live in Harford on the Beechwood Neighborhood of Haverford Township

- Philadelphia Transit Vehicles on the Norristown High Speed Line

- Rock Hill Trolley Museum “Independence Hall”

- The Trolley Dodger on the Liberty Bell Limited

- Article in The Morning Call in 1986 about the Liberty Bell Limited

- Ethan Lewis on Albert Johnson

- Philadelphia NRHS on the LVT

- Seashore Trolley Museum’s fund for the LVT 1030

One reply on “Norristown High Speed Line: Proudly Unconventional”

FWIW, the N5 cars on the NHSL were originally contracted in 1987 to a consortium of ASEA(the “A” in ABB) and Amtrak! The plan was to build them in Amtrak’s shops in Indiana.

However, that turned out to be a disaster and in 1991 ASEA, now merged into ABB Traction took over. However, their new American affiliate in Elmira, NY (now home to CAF) was too busy, so the work was subcontracted to Morrison-Knudsen in Hornell, NY (now home to Alstom’s train manufacturing division).

I was one of 4 different purchasing agents working for ABB inside MK, which was quite a blast! I was the primary point of contact on materials between ABB and MK. Had the project not started so poorly under Amtrak, these cars would have been the first in North America with AC propulsion (instead that honor went to the Baltimore LRVs built by ABB in Elmira).

What worries me about the N-5’s is that they were completed in 1994. I can’t find record of them being sent for overhaul and they are quickly approaching 30 years old. And they want to expand the line? With what rolling stock? SEPTA is lucky these cars are holding up so well, but realistically, they need to procure a new, larger fleet now.