Prior to introducing our subject today, let me first inform you that this draft had been incubating for an unacceptably long time. While working on this post during several different periods of time spanning a long period of time, I’ve felt many different feelings, from excitement, to curiosity, to dread, to indifference, but none of this matters since at this point, since, if I may say so myself, this might be one of the best accounts of New Orleans streetcars available on the internet.

Prologue

For years, every time I typed “streetcar” on my phone Gboard would autosuggest “named” and then probably “desire”. Same for Google searches. Fortunately at some point it learned that, to differ from the average English keyboard user, I type “streetcar” without looking for a play.

Why are you telling me this? you may ask. Well, apparently said play is set in New Orleans.1 From what I understand, partially thanks to this, the streetcars of New Orleans are very iconic. This image might hold them back, significantly, as the system operates with mostly semi-convertibles and semi-convertible replicas. They appear to have never seriously considered a vehicle much advanced beyond the 1920s! The system is absent of modern LRVs, but even 1930s streamlined streetcars like the PCC never held favor here. For a first gen system, that is unheard of, and to be honest, quite appalling. New Orleans is simply stuck in the past without trying to provide a modern transit service! Anyway, let’s check it out, maybe it’s not that bad after all, just weird.

Overview

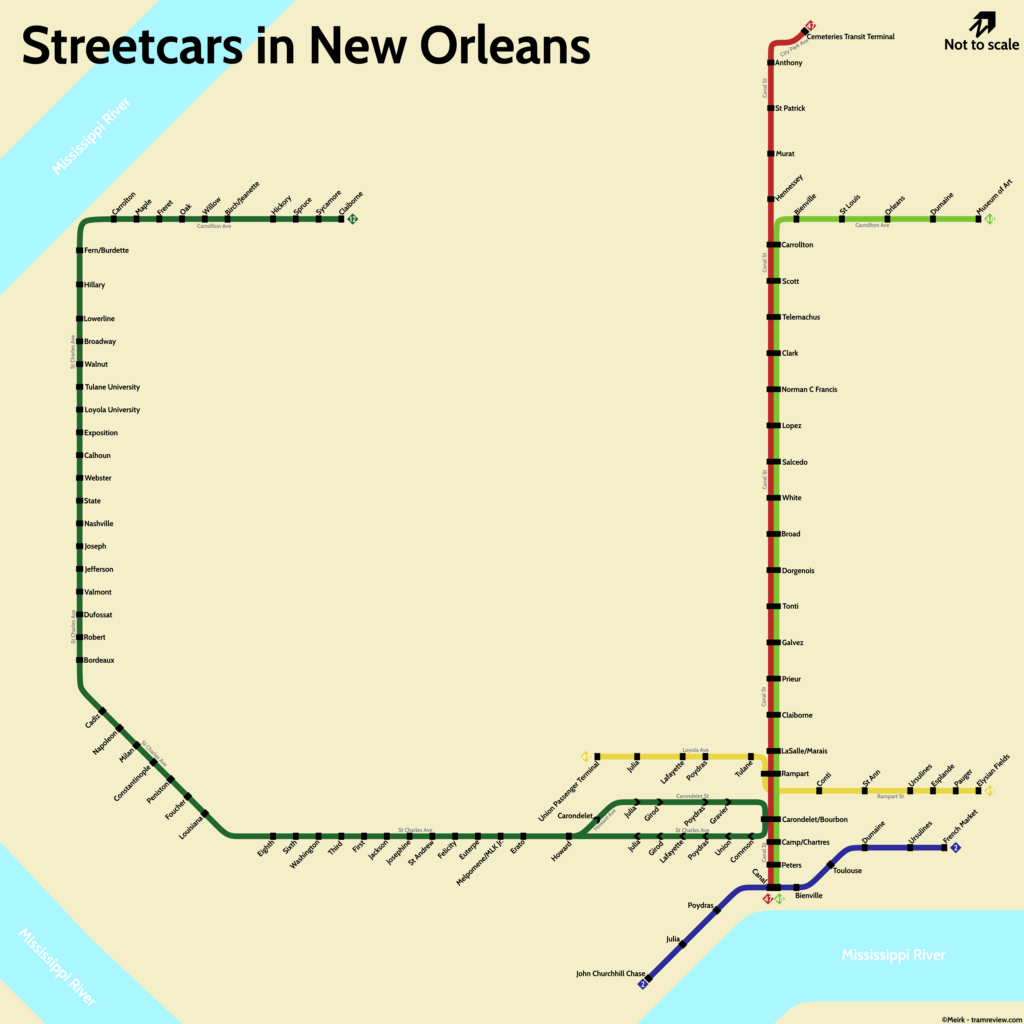

The traditional streetcar map of New Orleans, as you may find on the internet, looks like this:

Frankly, I like this interpretation of the system quite a lot, however as of Summer 2024, service patterns and line colors are quite different. The system currently looks like this:

As you can see there are significant differences in color, and some differences in service pattern. These will be explained later.

The system is composed of 5 lines, totaling 43.2 kilometers2 according to the Federal Transit Administration.3 For what looks like a fake-heritage system in the US south, the size is very respectable. When comparing to American systems of similar character, which tend to be second-generation, none of them reach this size. US systems of similar length include the Hudson-Bergen light rail, and Cleveland.

The system is of the Pennsylvania Trolley Gauge for some reason. We remarked multiple times on this earlier since it’s unexpected (as New Orleans is not in Pennsylvania, where all other systems using this gauge are).4 This gauge is 1588mm, is wider than standard, and is also used in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

The electrification is 600V DC, typical. It is important to note that the wires are designed for trolley pole use, as the streetcars are equipped with trolley poles. Considering this is a heritage system, this is fine, and frankly, more integrate than had they ran the same cars with pantographs. Though keep in mind trolley poles are overall less reliable and messier, which is why they have been superseded by pantographs where possible.

Rolling Stock

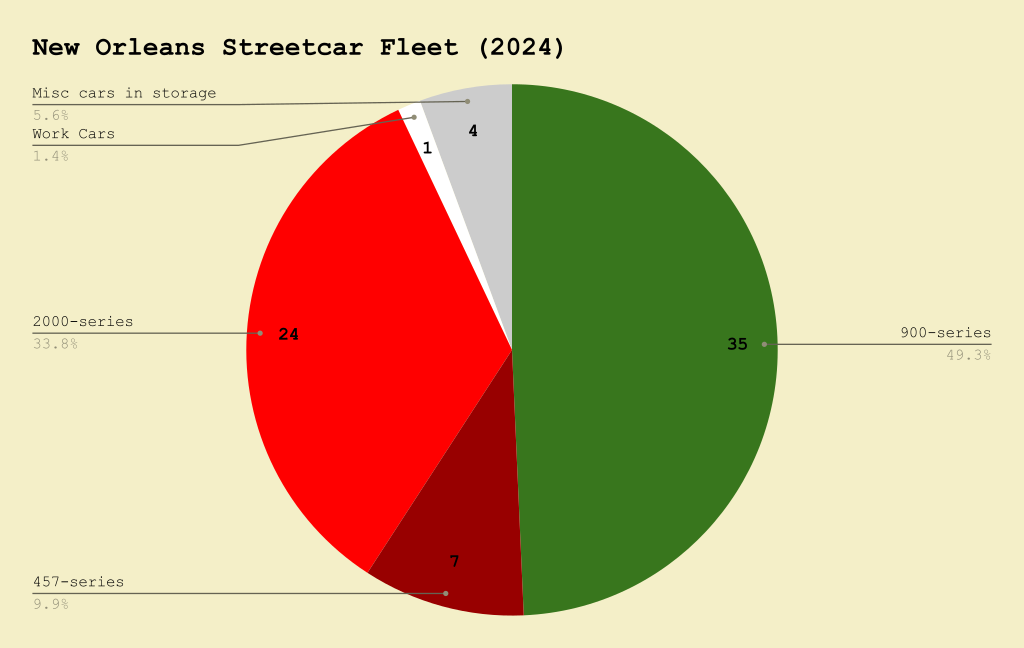

In New Orleans, you may find one of three types of streetcars in revenue service. Given that the fleet is, as of the moment, not seeing any changes, it can be nicely represented in a chart:

As you can see, the fleet consists of 67 revenue cars, split across three different types. The majority of the revenue fleet is the 900 series, with the 2000 series forming another core part, and the relatively small 457 series fleet making up the rest.

900 Series

Let’s start from the 900 series, there’s 37 of them and they were built by the Perley Thomas Car Works (today Thomas Built Buses), during 1923-1924. Their closest operating relatives are… in museums. 73 were built initially, and 35 remain in service with NORTA, with 2 in storage. They are non-articulated, high-floor cars, as expected from cars passing the 100 year age mark. They can be distinguished by their dark green color. They run almost entirely on the St. Charles line. During their long service lives the cars saw various retrofits, especially during the 60s, such as the replacement of wooden interior components with aluminium, a roof replacement for aluminium, plus what looks to be window and door replacements for a more current style. The cars were restored to a more original appearance by in the 90s.

457 Series

The second type of rolling stock in New Orleans is the 457 series (#457-#463). This is a small batch of 7 cars, one refurbished, the rest newly built. They were built starting 1996 for the rebuild of the Riverfront line. The first car was rebuilt out of car #957. They were built in-house by NORTA, with running gear from, unusually, ČKD. They are modeled after the old cars in looks, and as such are also non-articulated and high floor, but have a wheelchair lift.5 They can be distinguished by their red paint, however, in 2020, #460-#463 were repainted green to provide for accessible service on the St. Charles line.

2000 Series

The third and last series of cars in New Orleans is the 2000 series. These were built for the Canal line. They were built starting with a prototype in 1999, and a series following in 2002. There are 24 such cars. These were also built by NORTA in-house, currently with trucks from Brookville. They are similar to the 457 series in that they are colored red and have wheelchair lifts,6 but differ in that they have air conditioning. An explanation for this is provided by nycsubway.org:

Unlike the tourist Riverfront route, the Canal St. route is mainly a commuter line, and it would have been a hard-sell if they were going to replace air-conditioned buses and with hot and sweaty “vintage” streetcars.

Nycsubway.org: New Orleans, Louisiana

The cars can be distinguished relative to the 457 series by the more central position of their wheelchair lift, and their fake clearstory roofs.7 You might also feel the air conditioning.

Fares & Schedules

Here is a service table of the Summer 2024 schedule, which I believe is effective mid-May 2024:

| Service: | 12 | 46 | 47+488 | 49 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start Time: | – | 5:45 | – | 6:00 |

| End Time: | – | 0:05 | – | 23:45 |

| Morning Rush:9 | 15 minutes | 30 minutes | 11 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Midday/Afternoon: | 12 minutes | 30 minutes | 11 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Evening: | 20 minutes | 30 minutes | 11 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Night: | 30 minutes | 30 minutes | 20 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Trip Time: | ~45 minutes | 19 minutes | 47: 33 minutes 48: 33 minutes | 30 minutes |

After the rolling stock absurdities, this is significantly better than I would’ve expected. St. Charles and the trunk of Canal get reliable 24/7 service, while the railway station gets 15 minute all day service. I don’t think this would look out of place in Europe. The point of criticism in light of the frequent Canal trunk and St. Charles service is that branch service becomes inadequate really quickly: Riverfront and Rampart are half-hourly! For downtown routes that are not very long, NORTA could do better. There is similar criticism for the Canal branches, where on each branch service falls to every 22 minutes. While this is probably fine for the City Park branch, NORTA uses the Cemeteries loop as a transfer hub, where people are presumably expected to transfer from buses from the inner suburbs onto the 47 to continue into the city. Even though these frequencies are not ideal, they are quite respectable, and the absence of branch frequency is compensated by the overnight and extremely solid weekend service.

Fares here are the same as for the bus, $1.25, which I think is slightly cheaper than what’s common in large cities in the US, but not significantly. A single ride ticket does include a transfer window, though a day pass is available for $3 and NORTA appears to incentivize people to use it instead.

Fare payment is a simple mix of different methods:

- One can pay with exact cash on board, it is unclear whether a physical ticket is issued in that case.

- The schedule says you can pay with tokens, but honestly I doubt that given that the website gives it no mention and I hope tokens were phased out decades ago.

- A direct token replacement are the “Jazzy Pass” soft-card tickets, which can be purchased by mail, from a ticket office, or a ticket machine. New Orleans only has four ticket machines, all along Canal Street.

- NORTA also has a mobile app called “Le Pass”, which one can also pay with. This is the fairly primitive “moving circle” system (whereby the app opens a page with ticket information to visually show to the driver, complete with an animated circle to make sure you are not showing them a screenshot). The app looked very much like Moovit, and by switching my Moovit city to New Orleans I was able to get the same ticket purchasing interface.

- I was also able to add a NORTA pass to Google Wallet, no idea how that one works.

A mix like this serves all cases fairly simply, though it is complicated. This is typical of American mid-size cities. I feel like I expected something better from New Orleans, but maybe I am overestimating it.

Detailed Overview

Now, let’s go through the lines. Given current service patterns we will go by infrastructure. Services themselves are fortunately numbered like the buses, which is neat, and I wish more American cities did that.

But first, I must explain the discrepancy between the “traditional” services and current services. The services you will commonly find on maps are from when the system obtained its current state infrastructurally, in 2016. However, in 2019/2020, three things happened: Firstly, a building collapse at the corner of Canal and Rampart (the center of the system) took a large part of it out of service. Secondly, COVID-19 caused a crash in transit demand, and thirdly, either construction or a wire issue took the southern portion of the Riverfront line out of service. These events resulted in a significantly curtailed system for a while. By now everything except for the southern Riverfront line is back. This means services are back to normal except for that part, resulting in the 49 of today. I also suspect the different service colors we see are associated with NORTA’s 2022 bus route redesign. Anyway, that’s enough…

Pre-2019 services on the Riverfront line.

Current services on the Riverfront line.

Riverfront Line

The Riverfront line, traditionally numbered 2, is, coincidentally, 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) long, and runs along the “east” (northwest) bank of the Mississippi River. It contains 9 sheltered stops. The line is the only line in the system to run along a mainline rail right-of-way, and it follows it for its entire length. This means the line is also the only line to contain no mixed traffic, in theory providing consistent reliable service. However, most of the destinations along the line are tourist oriented and are lined with parking lots, and the line has historically never provided particularly frequent service.

The northern end of the line is at French Market station, just to the south of the intersection of Peters Street and Esplanade Avenue, and right next to its namesake. It is along the right of way of the New Orleans Public Belt Railroad. The station contains three terminal tracks, one of which merges then into the other two to form a double tracked line, next to the single mainline track. Awkwardly, the line is fenced off from the street for most of its northern part, and station signage on the street is lacking, counterintuitive for any line, and especially a tourist one.

The line continues to the southwest, stopping at the island platforms of Ursulines and Dumaine, before turning in a more southwardly direction to follow the river curve.10 The line then passes through the similar stations of Toulouse and Bienville. Right after that, the line crosses Bienville Street, the first road crossing on the line. The waterfront also becomes more touristic as opposed to the warehouses at French Market. However the line is still separated from the nearby city by a tall opaque fence.

Past Bienville the line goes almost directly south, and arrives at Canal station, which is also the terminus of the perpendicular Canal lines (47/48). Interestingly, there is no extra track to accommodate the terminating lines, which leads me to assume their actual terminus location is at the Harrah’s Casino stop about 100 meters to the west.11 The Casino no longer bears this name however the stop remains so on NORTA schedules. There is an aquarium and a plaza to the east of the station. This ends the northern section of the line.

After Canal, the line continues south, passing under the eastern wing of a hotel,12 and stopping at Poydras station. Interestingly enough, Poydras uses a side-platform arrangement, which isn’t found on the rest of the line. It is located near a continuation of the same plaza, and yet another hotel.

The next stop south, Julia, is next to a parking lot and what looks like a small cruise terminal. It is an island platform and is awkwardly inaccessible. It too is behind a fence. The terminal following it, John Churchill Chase, isn’t much different. It is not accessible from the street at all and is nestled between a convention center and the same cruise terminal, and is accessible from a footbridge linking the two.

Overall, while the Riverfront line may be separated from traffic, it fails to use that to its advantage, primarily connecting attractions to each other rather than to anything. The poor prominence and meager frequency do not help either. The southern end of the line being suspended for the past four years really shows how unimportant the line is in the end. However, NORTA using that to connect the line to downtown with the current 49 service is probably a good thing.

Pre-2019 and current services on the St. Charles line.

St. Charles Line

The St. Charles line, numbered 12, is 21 kilometers13 long, in loop length (meaning end to end is about half that depending on the direction of travel), and mostly runs along the median of St. Charles Avenue, with a section of one-way street running in downtown, and more median running on Carrollton Avenue on the other end of the line.

The inbound end of the line (as it is U shaped) is in downtown New Orleans, on Canal Street. The line’s downtown end is a one way loop, so this terminal is the end of it. It is a mere third track in the median shared with the Canal lines. The station seems to be a bus shelter on the opposite end of the median with not really much pedestrian guidance as to how to board, though fortunately enough the median is concrete so it is at least walkable.

From here the line goes down St. Charles Avenue, which is “narrow”14 in its downtown section. This section is one-way-outbound so there is one inbound track on the next street to the north, Carondelet, which is much the same. Due to the street running nature of the line, it would be reasonable to expect some simple stops, and indeed the stops are mostly quite simple along this section, with a bus shelter at most and a mere sign at least. It looks like there are a few curb cutouts but they aren’t very consistent.

This one way arrangement continues for about half a dozen blocks, then the track on St. Charles reaches Tivoli Circle and the track on Carondelet reaches Howard Avenue. The journey outbound would go straight counterclockwise over Tivoli Circle and into the median of St. Charles. The inbound meanwhile… Exits the median of St. Charles, and makes a three-quarters circling of Tivoli Circle before making a short journey on the median of Howard and turning onto Carondelet. Yes, you got it right, the inbound and outbound share tracks for a short section. This seems like a bottleneck, though line frequency probably doesn’t mean it is an issue.

I will note that there is track going both ways on Howard as far north Baronne Street, two blocks south of the UPT line on Loyola Avenue.

Past Tivoli Circle, the main portion of the line starts, along the median of St. Charles Avenue. It soon passes under the Pontchartrain Expressway, but remains entirely in the median of the avenue, as it slowly turns (or curves) northwards as the street grid copes with the turn of the river. The track is quite unaesthetically in dirt. Stations along this stretch are entirely short sidewalk patches whose main amenity is a trash can. I have to be honest to you this is quite disappointing. Jackson, Louisiana, and Napoleon differ in that they also have platform-end strips, a wider sidewalk, and bollards! Stop spacing here is a tight every-two-blocks, certainly better than Philadelphia’s every-block, but probably more frequent than it has to be.

By Carrollton Avenue, St. Charles Avenue fails to escape the Mississippi and reaches it in a weird intersection. The streetcar line continues, however, making a 90-degree turn from southeast to northeast onto Carrollton. The line here is much the same, though the stop here (Carrollton) gets curved platforms.

At Willow Street and Jeannette Street there are turnoffs to Carrollton yard, which services the line. The turnouts themselves are single track and go for about a block.

The line thus unremarkably reaches Claiborne Avenue, where there’s a two track terminal with a diamond crossover, and bus loops on other sides of the intersection. NORTA does appear to use this as a transfer hub, though the streetcar is by far the most frequent.

Overall the St. Charles line is a classic median tramway… with a downtown loop that’s a flashback to classic American streetcar route design. The line provides a frequent service on a defined corridor into downtown. It lacks crosstown service, isn’t direct end-to-end, and doesn’t really have good stations as expected from a median route. Outside of amenities and rolling stock, NORTA might want to increase transferability at Carrollton and Claiborne, so the line could provide two-way connectivity.

Pre-2019 services on the Canal lines.

Current services on the Canal lines.

Canal Lines

From observation, it’s fair to say that the Canal lines are the trunk of the system, and this statement holds true until you realize that the St. Charles line has better frequency. Anyway, these lines are a set of two lines consisting of a straight stretch down New Orleans’ main street, out from the river, through downtown, and onto mid-city, plus a branch to City Park (which appears to be a genuinely major and popular park). The total length of this thing is 8.9 kilometers.15 The line here is even simpler than the St. Charles, the street doesn’t even turn!

The lower end of the Canal line can be considered to start at the junction with the Riverfront line at the foot of Canal. Streetcars themselves, as mentioned, start a bit further onto the street at “Harrah’s Casino” (though as said the casino itself has been renamed, but the stop hasn’t). The 49 service currently does make this turn on its way to the Riverfront line.

From here, it’s straight along the median of Canal almost all the way. Notable things include a siding at the southern end, the loop of the St. Charles line at St. Charles Avenue and Carondelet Street, and then the double junction with the Rampart – St. Claude line at the neighboring Rampart Street and Loyola Avenue. This feels like a design oversight honestly, given that services here traditionally ran separately, and this results in the 46 service currently spending a single block on Canal, though this arrangement allows for better transfers, and despite it being mildly close to causing capacity issues, it probably won’t in the foreseeable future.

It is fair to say this ends “lower Canal” and now we continue to “middle Canal”. Density here really decreases as we exit downtown and cross under the highway that’s inside of Claiborne Avenue (same street as previously mentioned, believe it or not). Stop spacing is also wider.

At Prieur Street one can find the first island-platform station. Prior to this, all stations were side platforms in the median. The distance between the tracks in the median does slightly widen to accommodate this. The stops themselves here are all much the same. Some are mere concrete patches with a sign, but a lot get a shelter or at least a bench. Better than the St. Charles line, but still quite spartan.

Past Prieur Street, the median itself shifts from concrete to grass… though the line is really monotonous.

At Gayoso Street there is a turnout which leads to the carbarn which services the line, and which is located next to a bus yard.

At Carrollton Avenue, which is the same avenue which to the southwest is used by the St. Charles line, there is a junction. The 47 continues on Canal Street, while the 48 turns onto Carrollton towards City Park. This is where you could say “middle Canal” ends and “upper Canal” starts, as this part of the street gets half the service.

Past this point, everything on Canal is the same until Anthony Street, where, by the looks of it due to lane requirements, the southbound track is in traffic.

Canal Street itself reaches City Park Avenue, where it is discontinuous. The tracks make a sharp turn right, and then immediately a sharp turn left onto Canal Boulevard. Here there is a double-track loop in the median of the street. This short section is street-running.

As for the section on Carrollton, it’s slightly different: trams run in traffic with stops in the median. I am not sure if this causes reliability issues. Stops here do have something those on Canal don’t, which is tactile platform edge markings, which gives the stops a much more formal look, though they do lack shelters…

Now, this branch also ends when it meets City Park Avenue (New Orleans streets are weird, and City Park Avenue appears to be scary). The line shifts to to single track, and then doubles again before a stub island-platform, right at the southeast corner of City Park.

Overall, there isn’t much specific criticism for the Canal line from me, as it’s a clean and direct alignment with decent service. Now this doesn’t mean I don’t think service should be better, but what the lines could really do with other than that is the same as for the St. Charles line, namely rolling stock and stations.

Pre-2019 services on the Rampart – St. Claude line.

Current services on the Rampart – St. Claude line.

Rampart – St. Claude Line

The Rampart – St. Claude is the newest line on the system (2013/2016), and it can be seen. The line is 3.9 kilometers16 long. It is best described as two separate lines, one north of Canal Street (Rampart – St. Claude) and one south of Canal Street (Loyola – UPT). While the line is more intuitive to go through from southwest to northeast, I will do it from northeast to southwest, given that that the parallel Riverfront line was described in this direction.

While Rampart – St. Claude may parallel the Riverfront line, the line itself is quite different. The northeast end is at the intersection of St. Claude Avenue and Elysian Fields Avenue17 There, in the median of St. Claude Avenue, there is a double tracked island platform terminus complete with a shelter. The median running doesn’t last for very long, however, and the tracks are soon in the left lanes of St. Claude Avenue (on either side of a green median), for two blocks that is, since the avenue then makes a curve to become Rampart Street across an area marked as Joseph Guillaume Place (unclear if this refers to the curve or merely the intersection with St. Anthony Street along it). The line is generally the same from here on until Canal, but I would like to highlight that stops are well spaced and sheltered, a win over other lines in this regard.

After about 15 blocks, Rampart Street reaches Canal. The line here ends in a junction with the Canal line. But wait! I told you there’s a stretch on the other side of Canal, and indeed there is, it’s just one block to the northwest on Loyola avenue. I do not know why it was decided to build it like this, since as mentioned earlier this feels like a potential bottleneck, but I guess it works for now, and either way fixing it isn’t too complicated.

The section on Loyola, while a few years older, is similar though slightly different, namely the median on Loyola is much wider (though streetcars are still in traffic), and the shelters used are best described as “BRT-style” rather than the canopies on Rampart. This section is much shorter and soon reaches Howard Avenue, where the line turns into its own bay containing a double track terminus right next to the Union Passenger Terminal, which is New Orleans’ main train and intercity bus terminal. It is nice to see such a connection, though the streetcar does look shoehorned in there rather than particularly integrated.

Overall the Rampart – St. Claude line looks like a good urban line which is of significant enough length to be useful though not particularly long. Unlike other lines, it is not short on station amenities, though its insistence on being in traffic, especially on the Loyola Avenue section, confuses me. In terms of service, NORTA doesn’t provide particularly good service on its branches, though it does care about the UPT branch more than usual, with a good combined frequency on the 46 and 49. As said, the Rampart section with the 46 alone is less than satisfactory in my opinion.

History

Before we begin, I’d like to note that, from my understanding, there has been relatively little written about the history of New Orleans streetcars, which is weird given the relative renown of the system. One of the few books (if not the only book) written on the subject is Street Railways of New Orleans by E. Harper Charlton in 1955. This was later expanded and revised into The Streetcars of New Orleans with Louis C. Hennick in 1965. Fortunately enough, I’ve obtained copies of both.

I am aware that using a single source is problematic, and in fact, Hennick/Charlton omitted any mention of racial segregation on the system, though it did exist for significant parts of its history. For information about this, I will be using other sources, namely the 2020 academic book From Slavery to Civil Rights: On the Streetcars of New Orleans 1830s–Present by Hilary McLaughlin-Stonham, which while primarily using streetcars as an insight into the historical sociology of race in Louisiana in general, does provide specific information. I will not be explaining Louisianan sociology, but the souce is available on the internet if you’re curious.

Beginnings

Historiography of New Orleans streetcars, as established by Hennick/Charlton, traces us back to 1825, when talks of constructing a railway in New Orleans first appeared.

The Pontchartrain Railroad Company was chartered and started construction in 1830, and had its first journey in 1831. This was an “approximately 5-mile”18 route from New Orleans north to Milneburg, a small town on Lake Pontchartrain. This was one of the first railroads in the United States. As, on opening, the railroad’s steam locomotives had not yet arrived from the UK, the line used horses, and later switched to services ran by a mix of horses and locomotives.

But wait! How is this line a street railway? It didn’t run on the street, it didn’t possess any characteristics of a street railway, and in fact generally has the characteristics of early railways. I concede, I don’t know why it’s part of the streetcar history but I might as well let you know about it anyway.

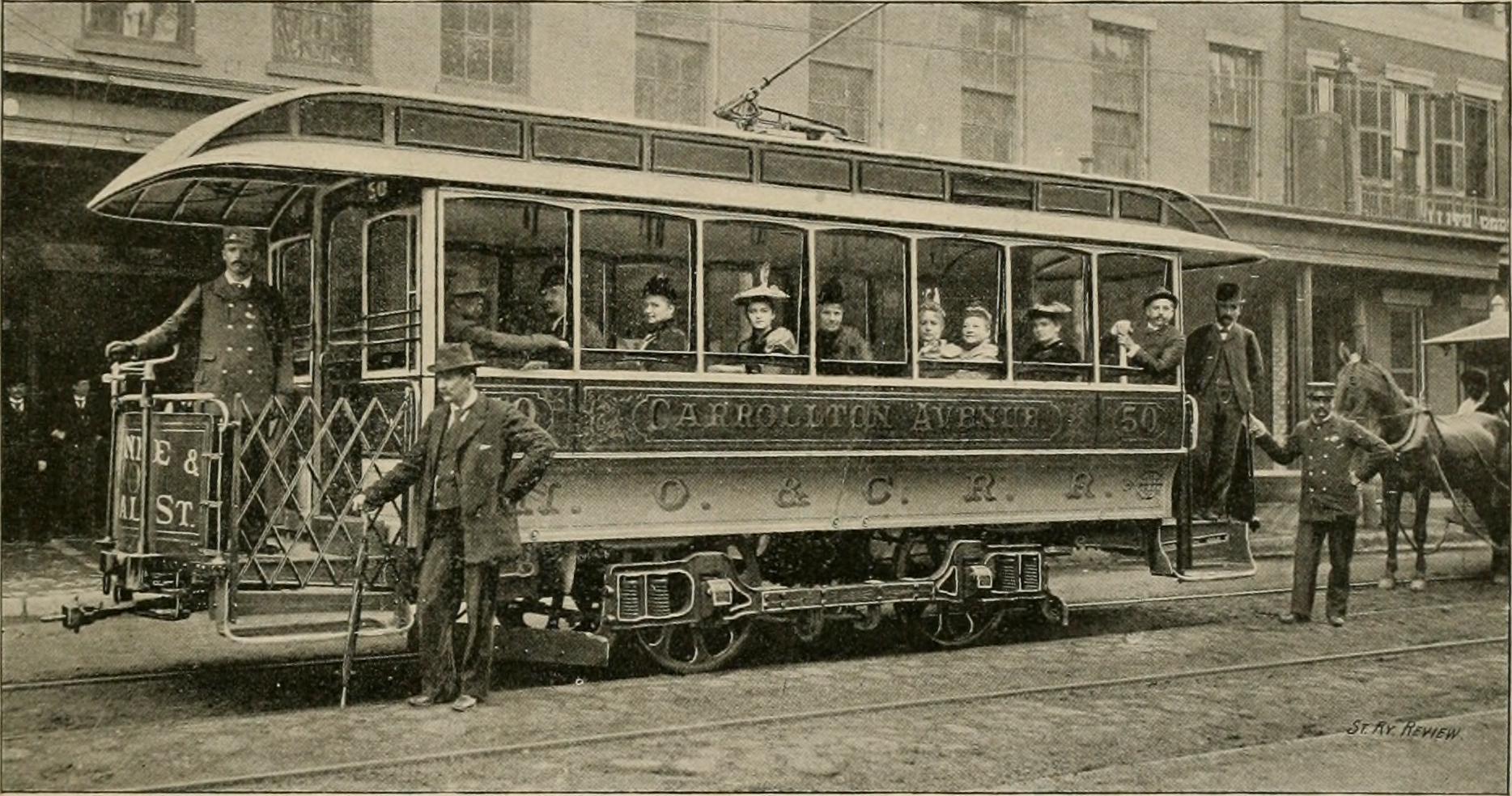

Now as for actual street railways in New Orleans, the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Company was chartered in 1833. This railroad commenced operations in 1835. This line ran from New Orleans to the suburb of Carrollton, also a distance of about 8 kilometers. This line had two branches.

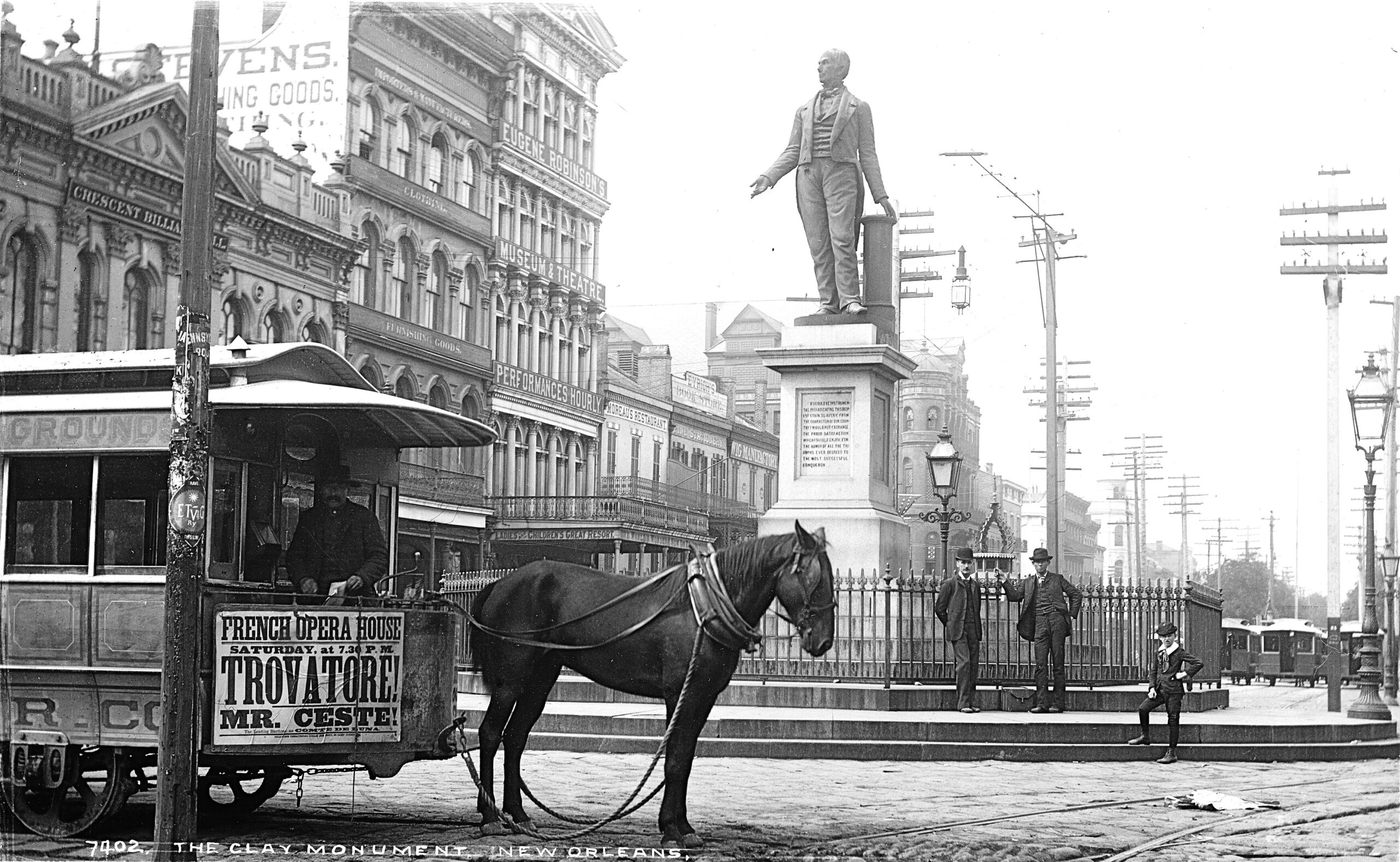

Now, this railway did actually posses the characteristics of streetcar. It ran in areas which were more urban, and did so on street medians, or “neutral grounds” in local terminology. This would make it the world’s second tram, after an earlier line in New York. Nonetheless, the line did also use a mix of steam locomotives and horsecars in its early days.

I would add here, horsecars in New Orleans were racially segregated from the outset, with most cars being White-only, and only cars marked with a star, that being “every third or fourth car” allowing all people. This was called the “star car” system. This was unsurprisingly resented and protested for its entire existence.

Following this there is a long period with mainly slight route changes and branch additions for the New Orleans & Carrollton. The company also acquired an existing charter for a second railway to Lake Pontchartrain. This was the Jefferson & Lake Pontchartrain Railway, commencing operation in 1853 using steam. It ran to a different point on the lake called Lakeview. It proved less successful than the Pontchartrain Railroad and was ultimately dismantled in 1864.

As a sidenote, the 1850s also saw intercity rail arrive to New Orleans.

Primary Development

Until 1861, the New Orleans & Carrollton was the only street railway in New Orleans, and it did not have a comprehensive network throughout the city. Hennick/Charlton mentions that this is a typical pattern of street railway development throughout the world and that “reasons for this pattern are not clear”.19 They also mention that horsecar networks at the time primarily served already built-up areas, and were not being used for development. Nonetheless, the network at this point only served the “American Quarter” of New Orleans (southwest of Canal Street), rather than the equally established (and older) French Quarter (northeast of Canal). Horsecars would not arrive at the French Quarter until 1868.20

The second street railway system to appear in New Orleans was the New Orleans City Railroad Company, chartered in mid-1860 by J.B. Slawson, the owner of several omnibus lines in the city. These lines were laid in, you guessed it, Pennsylvania Trolley Gauge, but Hennick/Charlton doesn’t explain why. Shipment of the first mule cars from New York in spring 1861 was delayed due to the US Civil War, but they did make it and the line opened in early June. The City Railroad company soon opened several other lines, creating a system.

It is not my duty to explain the US Civil War to you, but it did make an impact on street railway development. To put it very briefly: the war lasted from 1861 to 1865, saw New Orleans not be part of a United States for a short while before being under American occupation, and significantly hurt the city’s economy for that decade, by way of shipping interruptions and draining of funds.

The reconstruction era which followed the Civil War saw successful protest against the “star car” system, which ended in 1867. This was the byproduct of the social changes of the era and New Orleans’ political setup.

Street railway development continued after the civil war, albeit more slowly than it could have due to the economic conditions. The financially volatile Jefferson City Railroad Company started operations in 1864, and the far more successful Crescent City Railroad Company in 1866. Both of these were Pennsylvania gauge. A third company that started operations in 1866 was the St. Charles Railroad Company. An interesting thing about the last two is that they both commenced operations before they were chartered, a bureaucratic oddity. The explanation for this is that the city sold rights for the lines separately from the company chartering.

Steam locomotives were retired from the New Orleans & Carrollton in 1867.

As typical in American streetcar development, now proceeds a slew of line openings by separate companies. There’s a reason I don’t usually talk about those! Today I will continue as usual and spare you that. Of note is the continued use of the Pennsylvania trolley gauge for most new lines, the mixed use of mule cars and horsecars, and a few more instances of companies starting operations before being chartered.

The city approved of a resolution to display advertising placard on mule cars in 1868. Per Hennick/Charlton, this is the first instance of streetcar advertising.

New Orleans had a significant amount of experimentation with non-animal propulsion before the advent of electric propulsion. Notable experiments include:

- In 1866, by the New Orleans City Railroad Co.: A device which provided traction from a spoked wheel touching the ground propelled by the motorperson spinning a different wheel (this has to be seen to be understood).

- In 1868, by the Crescent City Railroad Co.: Pneumatic propulsion.

- In 1870, by the New Orleans & Carrollton: cable cars with overhead cable.

- In 1872, by the New Orleans & Carrollton: A small locomotive using ammonia for propulsion.

- From the same inventors, a more practical “thermo-specific” steam locomotive.

As you can understand, none of these were particularly destined for success, however they are important to note… even just for their absurdity creativity.

Hennick/Charlton provides a snapshot of street railways in New Orleans in 1874, companies, ranked from largest to smallest, were as follows:

- New Orleans City Railroad Co. (broad gauge, 141 cars, 12 million annual riders)

- New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Co. (standard gauge, 59 cars, 4.8 million annual riders)

- Canal & Claiborne Streets Railroad Co. (broad gauge, 40 cars, 6 million annual riders)

- St. Charles Street Railroad Co. (broad gauge)

- Orleans Railroad Co. (broad gauge)

- Crescent City Railroad Co. (broad gauge, 35 cars)

- Magazine Street Railroad Co. (broad gauge, 10 cars)

As you can see, broad guage predominated, as always with such things, we don’t seem to know why, but I guess it is foreshadowing. I am not sure if this pattern is typical, but it does portray the variety of different companies typically seen in large American cities in the 19th century (this is seven different companies!).

The 1870s saw the development of two additional suburban railroads to Lake Pontchartrain, one of which was Pennsylvania trolley gauge and ran by the New Orleans City railroad, though with steam dummies.

Electrification

By the 1880s, the very significant street railway expansion which I glossed over slowed down, but it did see events of significance for the the city’s street railways. The New Orleans Cotton Centennial Exposition ran in the southwest of the city from late-1884 to mid-1885. It contained two whole electric railway shuttles. The roughly 300 meter long railway of the Daft Electric Light Company, operated with third rail per the patents of the British Leo Daft, and a roughly 1.5 km long line using the technology of Charles Van Depoele, which, as readers of this blog may know, was trolleypole overhead wire. This no doubt caught the attention of the executives of the city’s seven street railways, or at least I sincerely hope it did!

In 1885 New Orleans saw its first streetcar strike: “hours and wages were the issues”. Hennick/Charlton doesn’t provide any further information.

Actually, let’s go back to the Centennial Exposition, I was wrong, the first attempts at electrification in New Orleans were done with battery!21 In 1889 the Crescent City Railroad Co. and New Orleans Railroad Co. chartered a company to manufacture battery-electric cars, but anticlimactically, the company appears to have not done anything. The Crescent City Railroad Co. also bought a car from the Gibson Electric Co. in 1889, equipped with their own batteries and a Daft motor. While such cars were successfully used in New York, in New Orleans the car failed. The Crescent City Railroad Company then proceeded to to award a contract to E.T.&M.Co.22 to equip 40 cars with batteries. At least one car was converted, but the program failed and the contract was annulled in 1892.

Only only now does Harper/Charlton tell me why I’m wrong: Apparently the city did not allow for overhead wire electrification. It took until late 1891 after a petition by the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Co., who sent an executive to observe and report on the electrified system in Richmond Virginia23 for the city to change its mind. The New Orleans & Carrollton started overhead electric service in February 1893 after slight delays. Even contemporary newspapers realized that this was quite a late electrification for a city of this size. The city’s other street railway operators quickly followed suit. The city’s street railway system, in addition to one of the lake lines, were fully electric by the 20th century.

In 1899 the Canal & Claiborne Railroad Co. was absorbed by the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Co.. The Canal & Claiborne converted to standard gauge during electrification. This merger also saw the introduction of a dark green and cream livery across the company’s lines, a livery which is still used today.

1899 also saw several of the city’s other streetcar companies by absorbed by the New Orleans City Railroad Co. (a new entity not directly related to the one mentioned earlier).

By 1900, with ongoing consolidation, New Orleans had four streetcar operators:

- New Orleans City Railroad Co. (broad gauge, 300 cars, 115 miles)

- New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Co. (standard gauge, 120 cars, 40 miles)

- Orleans Railroad Co. (broad gauge, 31 cars, 11 miles)

- St. Charles Street Railroad Co. (broad gauge, 40 cars, 12 miles)

Consolidation

I don’t know why I listed all of those since in 1902, all four companies were consolidated under “New Orleans Railways Company” (NORysCo), thus finally providing us with a single streetcar operator in the city. Unlike electrification, this is on-time with contemporary trends across the US.

September 1902 saw a 15-day strike of operating personnel. The matter was a renegotiation of labor agreements, a wage raise, and unionization. NORysCo eventually agreed to meet these demands.

In 1902 streetcars were once again resegregated as part of the rise of Jim Crow laws in Louisiana. I presume this was segregation-by-sign.

In 1905 the New Orleans Railways Co. went into receivership and was restructured as the New Orleans Railway & Light Company (NORy&LCo). Hennick/Charlton notes that this is odd given that the system appeared to be business as usual that year.

1906 saw the introduction of semi-convertible streetcars to New Orleans.

From here for a while the history gets a bit dry, with route changes, additions, and rolling stock changes…

1915 had a one-year dip in passenger numbers due to the introduction and quick prohibition of jitney services into and from the city.

In 1918, NORy&LCo was operating 555 motors cars (and 42 trailers) over 219 miles of track.

Also in 1918, NORy&LCo entered receivership…

In July 1920, the streetcars saw another strike, apparently primarily over wages. Strikebreaking efforts by NORy&LCo did not succeed and they had to concede to a wage raise after two weeks. Now I think I get why NORy&LCo was characterized as “austere”.

NOPSI

The New Orleans Public Service Incorporated (NOPSI) was chartered in 1922, and it took over streetcar operations in the city, along with power and gas services. From my understanding this was a private company.

Hennick/Charlton spends some time providing the testimonials of consultants surprised to discover the oddity of New Orleans travel patterns while studying them: unusually high demand during the night, and Mondays being as busy as Saturdays (that is, busier than normal). They don’t explain the former, but an explanation for the latter is the bargain day at department stores on Canal Street being on Monday.

In 1924, NOPSI started its first bus line, and streetcar lines started to be bustituted from 1925, bringing about the long and slow decline of the system.

Around this time there are instances of regauging of the standard gauge lines to broad gauge, though not all at once.

1926 is considered the peak of streetcars in New Orleans, with 248 million passengers riding on NOPSI’s 25 streetcar lines and five bus lines that year. Ridership would only decline from there. I don’t know if this is typical but it doesn’t seem unusual.

In 1928 NOPSI purchased the 1000 series streetcars from Perley Thomas and the St. Louis Car Company. This would be the last traditional streetcar acquisition in New Orleans. Feels early for a city of this size… and especially notable given that these cars would (evidently) be retired before the older 900s, and given that New Orleans would never acquire the PCC, which swept large cities throughout the US and Canada in the late 30s and 40s, apparently since it did not seem worthwhile neither when the PCC was new, nor when they could be bought used.

1929 was, per Hennick/Charlton “a disastrous year for public transportation in New Orleans”. What was the matter? Well, you guessed it. It was another strike. This one started in early July and was about, per Hennick/Charlton, “the company’s unwillingness to accept a closed shop provision plus stronger curbs on the company’s power to discharge men.” Strikebreaking attempts were apparently met with violence and were unsuccessful. Service returned in mid-August, but the strike did not formally end until the union voted to accept the mediation agreement in mid-October. This strike, as you can assume, cost the company dearly.

Also in 1929, amid the continued shrinking of the system, the last standard gauge lines were regauged to Pennsylvania gauge, though this wouldn’t be the last appearance of standard gauge streetcars in New Orleans.

Track mileage had shrunk to about 168 by 1931 and 148 by late 1932.

On the eve of World War II, which, as you know, “froze” railways’ service decline in the US, NOPSI had 109 miles of track and 243 cars. Meanwhile, NOPSI had 116 miles of bus or trolleybus routes. Streetcars, nonetheless, turned in 73.7% of company revenue, and had 58.3% of vehicle miles.

In large cities across the US, World War II saw a rebound in transit ridership, due to restrictions on rubber and gasoline, and I presume a change in travel patterns. New Orleans was member to this trend, with ridership peaking in 1945 with 246 million, just short of the 1926 record.

Postwar

Unsurprisingly, decline continued after 1947, with several heavier-ridership lines converted to bus in 1948.

In 1953, NOPSI had only 36 miles of streetcar track, though after 1953, only two streetcar lines remained, Canal and St. Charles.

Segregation on the New Orleans streetcar (and presumably bus) system ended once and for all in 1958 following a lawsuit by the New Orleans Improvement League, which generally happened uneventfully.

In the early 60s the remaining fleet of the 900s series saw refurbishment, in spite of their age.

In May 1964 the Canal Street line was converted to bus, in what Hennick/Charlton describe as a fairly somber ceremony. Given that this brushed by the date of publication of the book, you can see that the text is more sentimental. Hennick/Charlton proceed to mention that the median (“neutral ground”) of Canal Street was narrowed thereafter. They talk of the then-private (still!) company convincing the city of the superiority of buses, and the absence of action that was done to save the Canal line. They do however mention the small “Streetcars Desired” group which worked to save the Canal line to no avail.

This is where The Streetcars of New Orleans by Hennick/Chalrton runs out, as the book was written in 1965. As you can understand, 1965 was 59 years ago, and a lot has happened since then. Fortunately enough, in 2010 Earl W. Hampton Jr. wrote The Streetcars of New Orleans: 1964-present, which is designed to complement the previous book, and which I have also obtained a copy of.

Unsurprisingly, Hampton also starts with the closure of the Canal line. This appears to be a major historiographical node for New Orleans…

With the closure of the Canal line a few of the non-refurbished 900-series cars were dispersed to museums.

Lowpoint

Apparently the closure of the Canal line provoked enough outcry that NOPSI gave up on closing the St. Charles line. I am not entirely sure how that happened or what exactly happened.

Hampton remarks that 1970 was not a good year for the St. Charles line, firstly due to a vehicular collision in February, and then in April car 930 being badly damaged from a fire caused by a dewirement, which in turn happened as NOPSI was using trolleybus-style swivel poles at the time. What’s remarkable about this is, that despite significant damage to the car, it was rebuilt and back in service by October, showing NOPSI’s in-house construction capabilities. If this wasn’t enough, in July a car hit a pole at the end of the line at South Carrollton and South Claiborne due to a loss of brake pressure.

In 1971 NOPSI transitioned their streetcars to one-man-operation, meaning one crew member per car. This is extremely late for the US, and especially for a company characterized by stinginess, given that transition to this type of operation happened in order to save on labor costs. NOPSI actually planned to do it in the late 20s, on par with contemporary trends, however the city did not allow it at the time. Hampton mentions this as a reason the city did not acquire PCCs, as they were primarily designed to work with only an operator, however there were PCC variants which did allow for a separate conductor.

In 1973 the St. Charles line was put on the National Register of Historic Places (which doesn’t actually guarantee protection), and eventually the line would be made a National Historical Landmark. Unfortunately preservation protections in the US are hard to research so I can’t really provide details.

In 1983 NOPSI handed over public transportation operations to the public New Orleans Regional Transportation Authority (NORTA), thus ending the private operation of public transportation in New Orleans. This is, again, on the late end of things… For better or worse, this city just lags behind the times!

Hampton notes that in the 80s, the public attitude in New Orleans towards streetcars started to become very friendly, for whatever reason. Probably in line with this, and as part of this change, NORTA threw a party in September 1985 for the 150th anniversary of the system.

Revival

On August 14th 1988, NORTA opened a second streetcar line in the city: the Riverfront line. This line ran along the railroad trackage by the river, and was standard gauge and single track. Standard gauge? Yes, this line was not only isolated from the existing line at St. Charles, it was also incompatible with it.

For service on this line NORTA got four cars numbered 450-452 and 454.24 450 and 451 were rebuilt 900-series cars which arrived in the city during the 80s after being sent off in the 60s. 452 and 454 were Melbournian W2 class trams, a 20s center-entrance design. This type of tram was and remains popular with miscellaneous streetcar operations, as the W class was a very large standard fleet but upon its retirement most were not scrapped. These cars were refurbished specifically for the Riverfront line, but upon their delivery NORTA quickly brushed them up at their shops.

The line originally had only a single passing siding, but all four cars were typically in service, this resulted in a bottleneck and operational headaches. NORTA double tracked the line in the 90s, in addition to obtaining an additional Melbourne car (#455) and sourcing another 900-series back (renumbered #456).

Given that the line was isolated, a maintenance barn for it was built for it near the intersection of Tchoupitoulas and Napoleon, far out along the railroad. Cars were towed to this location by rail-equipped tractor. Storage of the cars themselves was done on the line proper.

In 1997 the Riverfront and St. Charles lines were connected via a relatively short section of track on Canal Street. This saw the regauging of the Riverfront line to Pennsylvania gauge and its integration with the St. Charles line, bringing a streetcar “system” back to New Orleans.

The Riverfront cars needed to be changed over to broad gauge, and only the Melbourne cars being accessible was a problem. NORTA decided to solve both of these problems at once, taking car 957, which they had sitting around, and fitting it with a wheelchair lift, renumbering it 457 and thus creating the 457-series. NORTA intended to do this with the other three New Orleans cars from the Riverfront line, however preservationists did not react positively to the inauthenticity of fitting a wheelchair lift in a 1920s car. NORTA therefore decided the build new cars completely new in-house, given that they had the capability. This brought us the other 6 cars of the 457-series. With all their in house capabilities, NORTA did have to get running equipment from somewhere, and therefore bought 9 PCC cars from Philadelphia for parts. A curiosity is Philadelphia car 2147, which made a single experimental trip out from Carrollton Yard to Lee Circle (today’s Tivoli Circle) and back. This would make it the only PCC to ever run in New Orleans. Unfortunately for NORTA, PCC equipment proved unsatisfactory, and I think they then sourced the ČKD equipment we know today. Following the introduction of the 457-series, the Melbourne cars were sold to Memphis.

Interesting note about ČKD though: Apparently in 1997, New Orleans trialed (with passengers) a Tatra T6C5, which was a modification of the Czech manufacturer’s then-current non-articulated tramcar model made to suit the American market. I assume ČKD was looking to expand its reach while catching up technologically to competitive levels,25 and NORTA just happened to be looking for this type of rolling stock in anticipation of restored Canal service. It is unclear whether NORTA intended to buy Tatras per se, but it looks like they were going to use ČKD running equipment, if it wasn’t for ČKD folding up by this time. This was the only instance that I know of of a Tatra running in the Americas! It is quite remarkable and very little known. The car eventually made it to Strausberg, a town east of Berlin where it appears to be to this day.

21st Century

The New Orleans streetcar system entered the 21st century with the revival of the Canal line in full swing. Track was being put up, and a batch of 24 cars for service on the line was being constructed. NORTA ended up sourcing Saminco equipment and sourcing parts locally when they could. This was the 2000 series, which as you know came with air conditioning.

On October 17th 2003, the first test car made its way up Canal and to Cemeteries. Revenue service started on April 18th 2004. The new line included the two branches we know today, and a new barn. It has been considered a success story.

On August 29th 2005 Hurricane Katrina passed through New Orleans, and with the city being low-lying and surrounded by water, the hurricane (through a sequence of events) inflicted severe damage and prolonged flooding on the city. Damage was so severe that, in fact, the city has still not recovered to its pre-2005 population, and the event remains in the American public consciousness. As for the streetcar system, flooding was mild on the Carrollton barn but severe on the barn on Canal. Meanwhile the St. Charles line saw severe damage (in particular to wires), while the Canal and Riverfront lines light. Therefore, on the return of service in late 2005, 900 series cars were towed to the Canal line and used there, while the 2000 series awaited rebuilding. Partial service on the St. Charles line returned late 2006 and full service late 2008. The system was brought back to normal with the return of the 2000 series in 2008/2009. This is when I think the 2000s series were fitted with Brookville equipment.

This is where my other book runs out (it was published in 2010), from here on… I’m reliant on the internet.

The first segment of the Rampart – St. Claude line, effectively a branch from Canal Street to Union Passenger Terminal, opened in January 2013. Service through-ran onto the Riverfront line until 2016 when the complementary branch on the other side of Canal opened. No new cars were acquired for this service.

In October 2019, an under-construction building at the intersection of Canal and Rampart collapsed, causing significant service disruptions to the Canal and Rampart – St. Claude lines. It took NORTA several years to return service, probably due to COVID-19 and other complications. Canal service returned by 2021, but Rampart service only returned in May 2024.

The southern portion of the Riverfront line has been out of service since 2020, it is unclear why. It is likely either nearby construction or a wire issue.

At this point in time, the future doesn’t appear to hold anything for the streetcars. You saw this isn’t a normal system, and it really doesn’t appear to be taken too seriously by NORTA. Anyway, let me not get ahead of myself.

Analyzation

So, I’ve had enough of this system, what do I think of it? Well, if you abstract from the subpar platform amenities and rolling stock, it’s not a bad tram system, of the classic type, and with adequate service. The joke is that, if you don’t, it’s not a bad decoration. This system being treated better than decoration, but not quite as good as transit has been bothering me. Sure, NORTA does treat these like an extension of their transit network, they properly integrate with buses, aren’t paralleled by them, get better service frequencies, and serve important corridors. However, the insistence on subpar rolling stock, lack of good stop amenities, significant parts of the system being suspended for long periods of time recently, and neglect towards harnessing the benefits of tram technology all show that there is some sort of unserious treatment going on.

If anything, this system is best described as “reactionary“, because as much as I am taking this term out of context, I believe it’s appropriate, since this system over the past thirty years has been kind of really about restoring a bygone era of extensive tram systems, rather than aiming for a better connected New Orleans and moving towards the future. To a degree, this process has been the opposite of Pittsburgh.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I personally do not believe the idea of a traditional tram is inherently invalid in today’s world,26 but a system should be considering the inherent benefits of tramway technology today and evaluating the role of trams as compared to buses in a transport network (something markedly absent in New Orleans). I think it says a lot that NORTA is currently considering a crosstown BRT for regional connectivity when they have trams27 right there! For a city that has been blessed with an extensive network of street medians, this is nigh absurd.

Anyway, good bones, mildly misguided outlook, those are the New Orleans streetcars.

Type

So, from all that ranting, we can get what we need here: this is clearly a Streetcar, and as much as it hides behind its odd rolling stock and there not being many of those around in North America, there’s no doubt about it.

Sources

The images have been credited to their respective owners in the caption of each image

Due to the unprofessional nature of this blog, sources will be cited in a simple manner, with no formats yet. Sources used are:

- Federal Transit Administration: Transit Agency Profiles- NORTA (2022 PDF)

- H. George Friedman Jr: Appendix III to The Streetcars of New Orleans – page aa

- Google Maps

- HawkinsRail: New Orleans Streetcars- Arch Roofed Steel

- New Orleans Regional Transit Authority:

- Nycsubway.org: New Orleans, Louisiana

- Railway Preservation: U.S. Streetcar Systems- Louisiana

- Wikipedia:

- From Slavery to Civil Rights: On the streetcars of New Orleans 1830s-Present, (2020) Hilary McLaughlin-Stonham. (ISBN13 978-1-78962-258-4) (PDF)

- PCC The Car That Fought Back, (1980) Stephen P. Carlson and Fred W. Schneider. (ISBN 0-916374-41-6)

- [Louisiana – its street and interurban railways, volume 2] The Streetcars of New Orleans, (1965) Louis C. Hennick and E. Harper Charlton. (predates ISBN)

- The Streetcars of New Orleans: 1964-present, (2010) Earl W. Hampton Jr. (ISBN13 978-1-58980-731-0)

Additionally, special thanks to: Jim Schantz, Tom Tello, Kevin Farrell, Kenyon Karl, and Leo Sullivan.

Also a mention for Wikipedian User:Infrogmation for uploading probably over half of CC New Orleans streetcar photos out there, that was incredibly helpful.

4 replies on “Streetcars in New Orleans: Between Decoration and Transit”

You’re back! Fantastic article as always!

Are you sure it wasn’t too long?

I’ll admit it was a smidgeon loquacious, but I still love your takes anyway! Also, yes, the portion of the riverfront line is closed due to construction overhead with a building (at least when I was there a few years ago). I think they’re interpreting the building into a new tram stop, too.

Wow, What an interesting read. Enjoyed it very much.