Prologue

So… first review outside the northeast! 🥳 Anyway, as part of our tour of first-gen systems in North America, we will turn to Cleveland next. Frankly, Cleveland has a fairly unusual system in that it does not derive from the city’s streetcar system, but rather from a unique semi-interurban operation.

If you don’t know about Tram Review, you can visit the about page. 😄

Overview

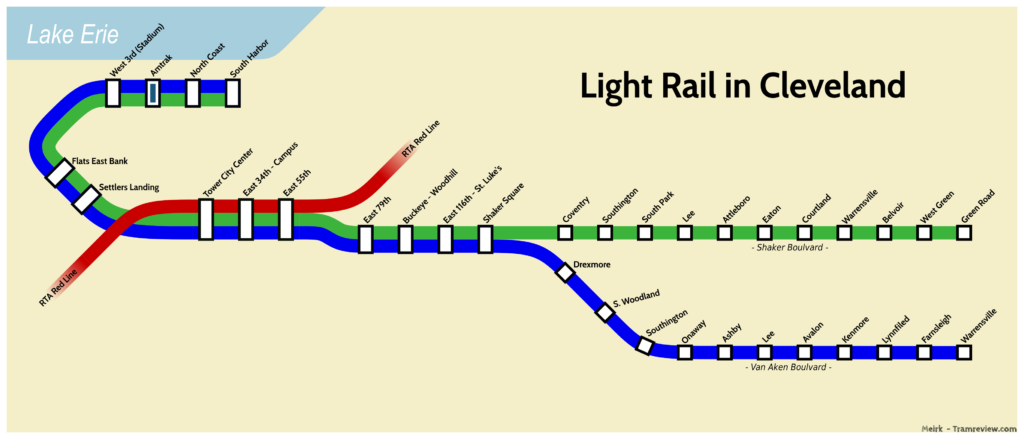

At 29 kilometers,1 this system is short for light rail systems of this kind, but it does reach into the suburbs, albeit only one of them. It is located in Cleveland, a city on Lake Erie in the northeast of the Midwest of the United States.2 The system consists of two branches that start at the waterfront of the city, then loop around the downtown core, where they share tracks with a subway line,3 then branch off of it towards the suburb of Shaker Heights. Splitting at Shaker Square, they both continue through the suspiciously wide medians of two different and parallel boulevards before terminating in the suburb.

Click here for a more detailed route description

The line starts in Cleveland’s waterfront, parallel to a railway, near the Lakefront airport. Later along the waterfront section, there is a flag stop as an interchange to the local humble Amtrak station, and a station serving the local American football stadium. Right before the railway crosses the Cuyahoga River, the line goes on a viaduct, passes by what looks like a planned but never constructed station, turns sharply southeast, and passes though the southwestern part of downtown at grade, serving two stations. Later there is a 90 degree turn north and a flying junction merge into the subway line tracks through the city center. There are three stations along this section, spaced far apart and grade separated.

Past downtown and some weirdly un-dense center neighborhoods, the line splits from the subway, once again at a flying junction, and climbs up a viaduct to reach The Heights. There are two stations along this stretch.

After reaching The Heights, the line enters into the wide median of Shaker Boulevard, where it is grade separated in a cut, and there’s only one station… At Shaker Square, the separation ends with the line crossing over two roads, then splitting into two branches, and exiting the Cleveland City boundaries into Shaker Heights.

The Green Line (67 internally) continues along Shaker Boulevard without grade separation until Warrensville, where the grade separation becomes inconsistent and the avenue ultrawide,4 before terminating in the leafiness at Green Road.

The Blue Line (67A internally for some reason) turns south along Van Aken Boulevard, and continues as it turns east. Except for crossing under Lee Road, there is no separation. The line ends at a commercial intersection at Warrensville Road.

In total there are 11 stations along both branches after the split, with the lines having about zero meters of street running. Other than the waterfront and downtown, the line is mostly in not especially dense suburbs. If I were to place 29 kilometers of LRT in Cleveland, this is not where I’d put them.

The system is standard gauge and is electrified at the standard tram voltage of 600 volts DC, and the entirety of the system is double tracked, but a lot is not grade separated.

The rolling stock is a fleet of 34 high floor (low boarding) two section articulated vehicles built by Breda in 1980. The vehicles are already 40 years old,5 and the RTA is looking for replacements. The vehicles replaced PCCs previously used on the system.

The fares on the system seem to be a $2.50 per one way trip, with 2.5 hour free transfers if you buy a 5-trip or more pass, but not with cash. Fares are paid at boarding going toward Shaker Heights, and paid when exiting when going toward downtown, which is different from the usual “pay when you get off going outbound”, but I guess it makes sense if there are faregates downtown. (wait, does that mean that suburb to suburb is free and you have to pay twice for in-downtown journeys? 🤔)

With the schedule, I’ll be standardizing the boring table, and then will opinionating it.

| Service: | Green Line (67) | Blue Line (67A) |

|---|---|---|

| Start Time:6 | 5:38 | 4:07 |

| End time:7 | 0:29 | 0:44 |

| Morning: | 30 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Rush Hour: | 30 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Midday: | 30 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Evening: | 30 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Saturday: | 30 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Sunday: | 30 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Trip Time: | 31 minutes | 32 minutes |

As you can see, the GCRTA is clearly joking to me, this is in no way “Rapid Transit!”, how dare they!

a while later

Oh wait! it’s a covid schedule! 8 and it lacks Waterfront service… uh, I’ll give them a pass this time, but they won’t escape from my perfectly reasonable frequency requirements next time!

Either way, considering the amount of vehicles, it looks like they can’t really run it more than every 20 minutes before they run out vehicles. Also the core section shared with the subway line is a major bottleneck. The areas served aren’t especially dense so the lackluster frequencies are pretty much expected here, not that it’s good…

History

Van Sweringen Era

As opposed to what you’d expect, Cleveland’s light rail does not derive from the urban streetcar system, but rather, as many things with a weird geographical focus, from a real estate project.

It all started in 1905, when the Van Sweringen Brothers (from now and on referred to as “The Vans” because I’m lazy), a pair of local real estate developers, were planning to develop the suburb of Shaker Heights.9 It was supposed to be an affluent, leafy “garden city” suburb with large homes and wide and curvy avenues. The suburb was incorporated in 1912, but it lacked one major thing: a convenient way to get into downtown.

Luckily, the Vans had planned the suburb with considerations for an “interurban” along Shaker and Moreland10 boulevards, with both containing generous medians for both lines, which were to be grade separated from their joining at Shaker Square towards downtown. The Shaker Heights Rapid Transit opened in April 1920, 7 years after an independently operating branch line on Shaker Avenue.11 It was operated by a separate company from the urban system of Cleveland (owned by the Vans), but used street trackage to get to the Public Square in downtown, as the grade separated line ended on East 34th Street. In 1929 the line along Moreland was extended from Lynnfield to Warrensville.

A major evolution of the system arrived in 1930, when the Cleveland Union Terminal opened, commissioned by the Vans (who went into the railroad business for it). It was a large intermodal structure on Cleveland’s Public Square. It was served by (most) intercity railroad traffic, and the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit, which entered into it along a railroad RoW, completely grade separated. In addition to being a major12 transit hub, it also contained a large commercial complex, and a 52 story office tower.13 The Vans also planned more interurban lines into the station, but those were never constructed.

The Shaker Avenue line was extended to its current terminus on Green Road in 1937.

Municipal Ownership

The Depression hit the Sweringen’s financial empire pretty hard, and the system was placed in receivership in 1935. The system seems to have continued as is until being sold to the city of Shaker Heights in 1944. The city did not exactly have the means to invest/expand the system, or maintain it for long, but it did bring in secondhand PCCs from Minneapolis starting 1949.1415

GCTRA

As noted earlier, the city of Shaker Heights could not maintain the line for very long due to limited resources. By the 70’s the Cleveland Transit Service, which operated the rapid transit line and buses since 1942, was also financially unsound due to the vicious cycle of declining ridership and investment/service. In late 1974, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (GCRTA or RTA for short) was formed, and it was county owned and funded by a sales tax, a rather effective but unusual system for North America.

The GCRTA took control of the CTS and the Shaker Heights system on September 1975. A rebranding of the lines followed in 1979, with the Shaker Line becoming the Green Line, and the Van Aken Line becoming the Blue Line, and the rapid transit line became the Red Line.

A major reconstruction of the lines happened in 1980, which included the replacement of track and wire, a modernization of all stations,16 the procurement of the Breda vehicles used today, and the retirement of the PCCs.

The light rail system was extended past the Union Terminal in 1996. This extension, called the Waterfront Line, had trains run through Union Terminal (by this time no intercity trains had served the station for 20 years, which has since been rebuilt and renamed the Tower City Complex), under the Red Line in a flying junction, at grade through downtown, and next to a railroad right of way along the front of Lake Erie. The extension serves major attractions on the lakefront, including a few museums, the American Football stadium, and the Amtrak station (which is a small building seeing two trains a day but whatever).

Analyzation

This medium sized suburban system looks neat, but is it practical?

Frequency: Excuse me?! what do you mean frequency! no such thing here. Maybe I’ll make a schedule review when it will be more normal.

Intermodality: The GCRTA’s fare seems is luckily better than the NJT’s. However this system isn’t exactly designed for transfers, though they are possible. A universal “load and use” card might be better than a “by trip” punchcard. The lines’ weird faregate structure, while dwell time reducing, is a bit… inflexible, with suburb to suburb trips breaking it.

Character: This system is interesting in that it is a first generation system that also broadly utilizes railroad right of way. The grade separation may be inconsistent, but it is appropriate, guaranteeing relatively stable travel times.

The line consists mostly of median running in Shaker Heights, and paralleling railroad RoW to downtown, a short streetside section through it, then more railroad RoW.

Type

The Cleveland system is not that far away from what I define as light rail, it is low floor,17 it uses median running, is grade separated when necessary, and runs parallel to existing tracks in places. The lack of street running certainly gives it a faster service than calmer systems, and the line serving mostly suburbs and the ones of Cleveland not being particularly dense would qualify it as Suburban Light Rail.

Sources

The images have been credited to their respective owners in the caption of each image

Due to the unprofessional nature of this blog, sources will be cited in a simple manner, with no formats yet. Sources used are:

- Google Maps

- The respective Wikipedia pages of what has been reviewed:

- The RTA website

- Case Western Reserve University Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

- Jon Bell on Shaker Heights Rapid Transit

We hope you have enjoyed this post, if you have any questions, comments, feedback? please do not hesitate to comment or contact us.